Upcoming webinar

Join me for an upcoming Strafford live webinar, "Design Patent Enforcement" on Thursday, February 18, 1:00pm-2:30pm EST. Click this link for more information: https://www.sp-04.com/r.php?products/tlhpvahkra

Join me for an upcoming Strafford live webinar, "Design Patent Enforcement" on Thursday, February 18, 1:00pm-2:30pm EST. Click this link for more information: https://www.sp-04.com/r.php?products/tlhpvahkra

On December 14, 2020, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California handed down a Claim Construction Order for 2 design patents that raised the interesting question: when is a line not a line?

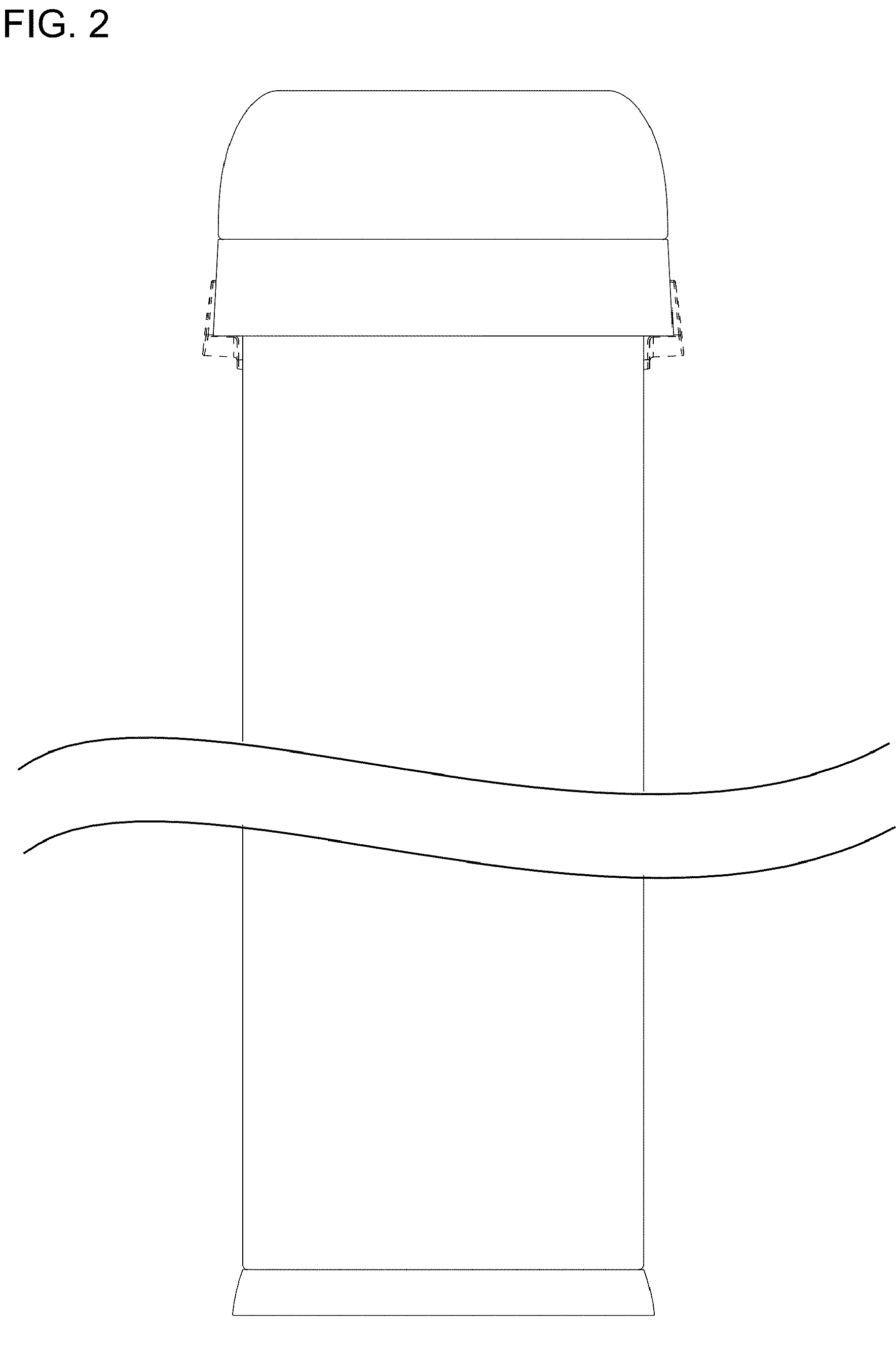

The case is simplehuman, LLC v. iTouchless Housewares and Products, Inc. (4:19-cv-027-HSG). The two design patents in play were D644,807 and D729,485. Since the issue is the same in both design patents, it will suffice to use one as an example. Following are Figs. 1-4 from D644,807:

The patentee simplehuman took the position that the various lines in question were contour lines; the accused infringer said they were “seams”, i.e., ornamental features that would need to be taken into account in determining infringement. The court created an annotated version of Figure 1 to “point out the disputed lines” of the ‘087 claimed trash can:

I’m guessing here (ha), but I’ll bet that the defendant’s product is devoid of such lines! To any design patent practitioner the lines in question are so clearly contour lines as to be beyond debate. They are commonly referred to as CAD lines or wire frame lines. Such lines do not generally comply with the USPTO’s drafting rules (time to update those?). Nevertheless, the USPTO routinely accepts drawings with such lines, because everyone knows that they represent contour and cannot possibly be ornamental features. The patentee nevertheless made a mistake in not having its draftsman either remove those lines entirely and/or replace them with standard shading before filing.

Another (practical) reason to remove those lines is that the resulting claimed design will look more like an actual product, rather than a confusing mess. A properly drawn product will be more easily compared to an accused design, especially by a jury.

The court said that the dispute in this case is resolved by the specification, saying “The illustrations in the design patents show the disputed lines in views where they cannot possibly represent shading.” This is the court’s logic:

1. The disputed lines occur on the right side of the trash can (see Fig. 1).

2. The top view of the trash can (Fig. 4) suggests an oval shape where the right side is largely flat.

3. Fig. 2, the front view, confirms the general flatness of the right side.

4. But Fig. 3, the right side, includes the disputed lines around the center.

The court is correct about all four of its observations (but for the “But”). How does that logic result in the disputed lines being called lines and not contour lines? Beats me.

Again, any experienced design patent practitioner knows that those lines represent areas where the underlying surface changes from straight to rounded. Standard stuff.

The court actually admitted that:

“At most, the disputed lines thus represent a delineation between rounded and flat surfaces.”

The court then discounted what it just said: “[T]hat does not suffice to show contour because it does not indicate which surface is receding (because it is curved) and includes lines in views where there would be no contour differences (the top down views).”

Interpretations to the previous quote welcome; feel free to post a comment to this blog.

Bottom line? Take out those damn CAD/wire frame lines before filing. And if there’s any doubt about the shape of the resulting design, have your draftsman insert some standard surface shading.

Simple, humans, right?

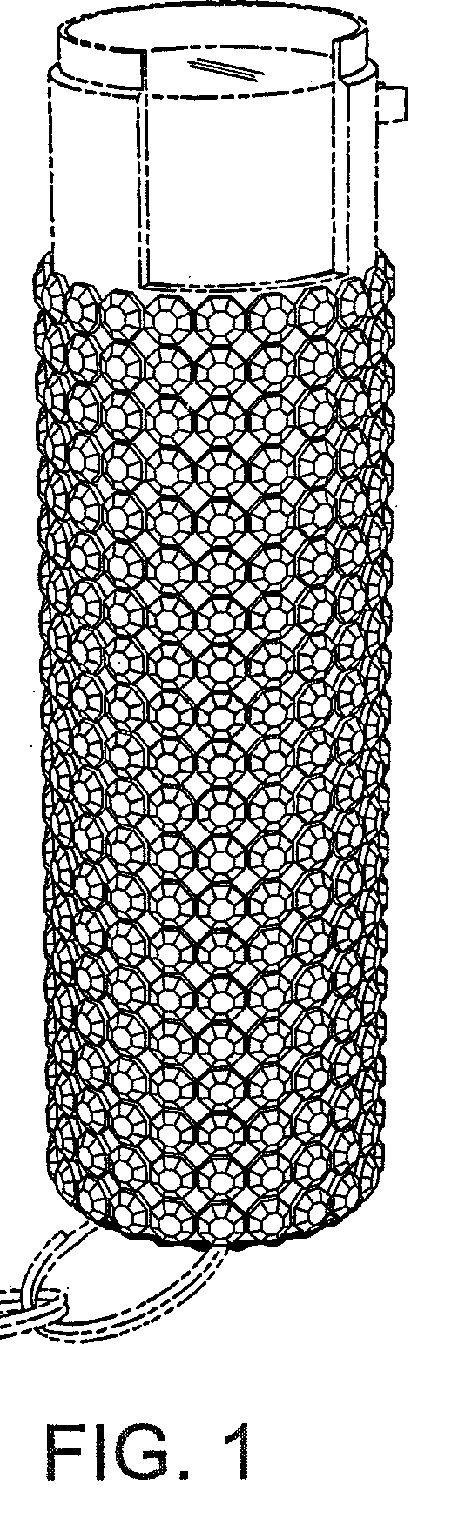

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on December 11, 2020 handed down Super-Sparkly Safety Stuff, LLC, v. Skyline USA, Inc. (Case No. 2020-1490). In a non-precedential opinion, the Court reviewed de novo the lower court’s decision granting summary judgment of non-infringement. The Court found no infringement under the ordinary observer test in that the patented and accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” and “sufficiently distinct”, which did not require consideration of the prior art. Even if not “sufficiently distinct”, the Court found that there was no infringement when taking into account the prior art as commanded by Egyptian Goddess. The design claimed in the asserted U.S. Pat. No. D731,172 was for a “Rhinestone Covered Container for Pepper Spray Canister”.

Below are illustrations of the perspective and bottom views of the ‘172 patent, the accused design, and the closest prior art “Pepperface”.

PATENTED DESIGN

PATENTED DESIGN - BOTTOM VIEW

ACCUSED DESIGN

PEPPERFACE PRIOR ART

The parties had agreed that the difference between the patented and accused designs was that the former claimed the rhinestones on the bottom of the canister, whereas the latter did not. The Court found that removing the rhinestones from the bottom surface was a “significant departure” from the claimed design, resulting in sufficiently distinct designs even when not considering the prior art.

Then the Court admitted that there were not many examples of prior art designs, but nevertheless the prior art Pepperface reference had rhinestones “around the majority of the canister”, but not on the bottom. Citing Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, the Court then said:

“[The] attention of a hypothetical ordinary observer conversant with bedazzled pepper spray canisters would be drawn to the presence or absence of rhinestones on the bottom of the cylinder.”

This is reminiscent of the old “point of novelty” test that was abolished by Egyptian Goddess. That is, the Court essentially said that having rhinestones on the bottom was the point of novelty that distinguished the patented design from the prior art, and since the accused design did not have that point of novelty, there was no infringement. It did appear that rhinestones on the bottom was indeed novel, since it was not found in the Pepperface prior art, nor the closest prior art of record, U.S. Pat. No. D667,999. So, are we now reverting to the old Litton “point of novelty” test?

Another significant point is this. This case was decided on summary judgment, i.e., the court concluded that there were no material facts in dispute, meaning no reasonable jury could find in the non-movant’s (i.e., the patentee’s) favor. But is that true?

I have previously ranted and raved about the unfairness of a “sufficiently distinct” finding that allows a court to ignore the prior art. For one thing there’s no objective way for a court to determine whether two designs are sufficiently distinct, and for another, there’s always prior art that’s relevant to the infringement analysis. A court finding that a patented design is “sufficiently distinct” from an accused design effectively steals the patentee’s right to a trial by jury on the ultimate issue of infringement. Whether the prior art is closer to the claimed design or accused design is a question of fact, ideally suited for a jury. A holding by a court on summary judgment that the two designs are “sufficiently distinct” prevents this question from ever coming before the jury.

Moreover, in this case, it’s not so clear that the patented and accused designs were not substantially the same in overall appearance. In the ‘172 patent, the rhinestones cover the canister all the way to the bottom edge, as they do in the accused product. However, in the Pepperface prior art, the rhinestones only cover a portion of the outer cylindrical surface of the canister; the rhinestones are centered on the cylinder, leaving exposed portions of the cylinder both at the top and bottom. Surely, in light of the fact that the rhinestones in both designs extended all the way down to the bottom, a jury could find that the patented and accused designs are closer to each other in overall appearance that either is to the Pepperface prior art, in spite of the differences on the bottom of the canisters.

Indeed, what is the difference between the bottom not having rhinestones and a portion of the cylindrical surface of the canister not having rhinestones? Either way, rhinestones are missing.

The court did not mention the prosecution history of the ‘172 patent. It reveals that the examiner found that the application disclosed 4 embodiments (Figs. 1-5, 6-8, 9-11, and 12-14). Each of these embodiments claimed a different length of rhinestones on the outer surface of the cylindrical canister. The examiner concluded that the 4 embodiments were patentably indistinct, i.e., basically the same, commenting that “the differences between the appearances of the embodiments “are considered minor”. Clearly, if the 4 embodiments are basically the same, even if they have a different length of rhinestones on the exterior, an argument could have been made that they are basically the same as the accused design. The absence of rhinestones on the bottom - had it been claimed - would very likely have been considered by the examiner to be basically the same as embodiments that had rhinestones on the bottom. Since “basically the same” is virtually indistinguishable from the “substantially the same” test for infringement, the prosecution history made out a plausible argument for a finding that the defendant’s design infringed the ‘172 patent.

It could also be argued that the ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives (as required by Gorham and Egyptian) would pay scant attention to the bottom of the canister rather than the exterior cylindrical surface. After all, it’s the exterior surface that gets advertised, noticed at the point of sale, and held by the user (note that of the 6 illustrations in the Pepperface ad, none showed the bottom of the canister). It could easily have been found by a jury that the exterior cylindrical surface is the dominant visual component noticed by an ordinary observer “giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives”, who may not even notice whether the bottom is covered with rhinestones.

In reviewing past case law, little attention has been paid to the Gorham and Egyptian requirement to consider what a purchaser would do, in contrast to the clear wording of the test for infringement:

“[I]f, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other.” (emphasis added)

Thus, in analyzing infringement there should be an inquiry into what attention a purchaser usually gives when buying a product. For example, when buying a refrigerator or TV, does the purchaser pay attention to the bottom, sides or back of the product? Even if those elements may be claimed, they are generally not dominant features viewed by a purchaser who would likely focus on the front of the product. Does a purchaser pay attention to the visual appearance of the insoles of Crocs shoes (see Int’l Seaway)? Does a purchaser pay attention to the visual appearance of the bottom of a shrimp container (see Contessa)? Would a purchaser pay attention to the top of a ceiling fan (see Fanimation)? These are legitimate inquires under both Gorham and Egyptian, yet the cases are silent about this requirement.

It is curious that the accused infringer was represented by Robert Oake, the same attorney who represented Egyptian Goddess back in 2008. This time, Mr. Oake was arguing non-infringement, while in Egyptian he was arguing infringement. While Egyptian was very significant regarding the issues of design patent claim construction and the abolishment of the point of novelty test, the patentee nevertheless lost on the merits. Its patented nail buffers, having pads on 3 of the 4 sides of an elongated, square, hollow body, was found not to be infringed by a nail buffer having exactly the same elongated, square, hollow body but with 4 pads, one on each side, instead of 3 as in the claimed design. The patented and accused designs in Egyptian, and the closest prior art, are shown below:

EGYPTIAN GODDESS

Note the following: the patented and accused designs are both elongated rectangular, hollow squares having pads on their sides; no prior art reference taught that appearance. The Falley reference was solid with no pads. The Nailco reference was elongated and hollow, but triangular. Even though Nailco has pads on all 3 sides, any ordinary observer would see that the patented and accused designs are closer to each other than to the Nailco prior art. Whether one of four pads was missing or not is relatively minor, and is probably not visually important to an ordinary purchaser. Three vs. four pads may be important functionally, but visually the two designs could easily be found substantially the same in overall appearance. What did the Federal Circuit say in Egyptian?

“[U]nlike the point of novelty test, the ordinary observer test does not present the risk of assigning exaggerated importance to small differences between the claimed and accused designs relating to an insignificant feature.”

Yet, in the present case, the Court did exactly that: assigned exaggerated importance to a minor difference – the presence or absence of rhinestones on the bottom of the canister, that an ordinary purchaser would likely pay little or no attention to.

The facts in Super-Sparkly are fascinatingly similar to those in Egyptian, and both cases involved Mr. Oake as counsel. And in both cases the lower court granted summary judgment motions of non-infringement. In Egyptian, one side of a design had something missing (the patented design was missing a pad), and in Super-Sparkly, one side of a design had something missing (the accused design was missing rhinestones). Maybe Mr. Oake learned from Egyptian that siding with the missing side was the side to be on!

Perry Saidman is available to present private seminars on design patents to your in-house group of lawyers and/or designers, either in person or virtually. As a former professor teaching Design Law at the George Washington University Law School, and as a preeminent figure in the design patent bar, your group can greatly benefit from Perry’s experience and expertise. His c.v. is here.

In a half or full day session, Perry can cover key design patent topics like obviousness, anticipation, functionality, infringement, damages, double patenting, including recent case law. He can also cover design copyrights and/or trade dress protection.

As an option, Perry can provide strategic feedback and advice about your specific cases, either issued, pending, or planned in the future. The seminar can be tailor-made to your individual wants and needs.

For further information, contact Perry at ps@perrysaidman.com

Further to my post of August 15, I’m attaching the slideshow I presented at the IPO Annual Meeting last month which suggests amendments to the design patent laws, to bring them into the 21st century.

The design patent laws have never been amended; the current version was adopted with the 1952 patent act. Clearly, it’s time for an update.

A subcommittee of the IPO Industrial Design Committee has been formed to consider possible legislative updates to deal with various issues that have arisen in the caselaw, long overdue.

Comments are welcome.

This is a bit different from my usual design law posts (actually, a lot different), to introduce you to an organization I have belonged to for many years – the Project for Integrating Spirituality, Law & Politics (PISLAP).

News and social media sources have been filled recently with news of the passing of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Often it is only after someone dies that their true legacy is appreciated. Maybe with the passing of this remarkable lawyer, aspirations to transform and reimagine the profession are being ignited. This quote of RBG’s stands out: “I tell law students… if you are going to be a lawyer and just practice your profession, you have a skill—very much like a plumber. But if you want to be a true professional, you will do something outside yourself… something that makes life a little better for people less fortunate than you.”

In a nutshell, that is what PISLAP is all about.

A new edition of The Conscious Lawyer, published by Elaine Quinn in London, and produced in collaboration with PISLAP and co-edited by PISLAP co-founder Peter Gabel, has just come out. The issue contains a wonderful diversity of subjects, from Ross Brockway's excellent article about the Georgia Justice Project's visionary representation of a client trapped in the maze of punitive child support laws, to Femke Widjekop's hopeful description from Holland of the new and healing "green criminology," to Jenipher Jones's discussion of the consciousness-elevation of Contemplative Lawyering, to Elaine's thoughtful review of Rhonda Magee's recent book The Inner Work of Racial Justice….all PISLAP members!

Please do read the issue, share it with friends, and consider joining PISLAP as a member and become part of a group whose influence and membership is expanding towards building a new and more humane and caring legal system.

This case is significant only because the USPTO cannot seem to print the drawings in issued design patents with a sufficient degree of clarity. For many design patents, there is a huge degradation in image quality between the drawings originally filed by an applicant and those that are printed in the issued patent. This has been a longstanding problem.

Originally filed high-resolution drawings are routinely stored in a USPTO database called the Supplemental Complex Repository for Examiners, or SCORE. Design patent Examiners use the SCORE drawings to examine the application. Once the patent is allowed and printed, many of the high resolution SCORE drawings have undergone a presumably unintended metamorphosis into unintelligible, highly pixilated drawings, where it is frequently impossible to distinguish between a broken line and a solid line; this is important, obviously, because solid lines define the claimed design, and broken lines define unclaimed subject matter. For design patent applications filed with high quality photographic images, the images in the printed patents frequently are out of focus, out of contrast, and simply look awful. Many examples abound.

Woe is the patent litigator who must assert one of these terribly printed design patents in court. How is the judge supposed to determine the meaning and scope of a design patent claim that on its face, i.e., on the face of the printed patent, have drawings that are unintelligible and thus arguably indefinite?

One court has offered a path out of this mess. In Panasonic Corp. v. Getac Technology Corp. et al., the district court for the Central District of California considered whether to incorporate the SCORE drawings of the 4 design patents at issue into its claim construction.

In the illustrations below, on top is FIG. 19 of the original SCORE drawings of Panasonic’s U.S. Pat. No. D766,232, while on the bottom is the same figure as printed in the ‘232 patent. The problem is manifest.

The defendants contended that the patents were indefinite because of the lack of clarity in the printed patent drawings. The patentee Panasonic responded by asking the court to rely on the SCORE images to determine the scope of the patents in issue.

The Defendants argued that the court could not substitute file history drawings for patent figures, and cannot correct any errors in a patent that are not evident on the face of the patent. More particularly, the Defendants argued that an ordinary observer of a design patent would not have understood that the SCORE drawings (and not the figures on the issued patent) defined the scope of the claim because there was no mention of other drawings in the patent specification. Defendants also argued that Panasonic chose not to correct its patents using a Certificate of Correction, choosing instead to sue the Defendants on patents “they knew were defective”.

There is no dispute, the court said, that the SCORE drawings are part of the prosecution histories, and that the Patent Act requires “a patent’s claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history” to “inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty”, citing the 2014 Supreme Court decision of Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.

Interestingly, the court cited the test from In re Maatita which said that a design patent is invalid for indefiniteness under Sec. 112 “if one skilled in the art, viewing the design as would an ordinary observer, would not understand the scope of the design with reasonable certainty based on the claim and the visual disclosure”. The court also relied on the Federal Circuit decision Phillips v. AWH Corp. that said claim construction is provided in view of “the claims themselves, the remainder of the specification, [and] the prosecution history.”

The district court had no trouble in construing the claim of the ‘232 patent as follows:

“The ornamental design for a portable computer, as shown and described in Figures 1-20 of the patent and Figures 1-20 located in the D’232 Patent file history and available through the Supplemental Complex Repository for Examiners (“SCORE”) database. The broken lines shown in the figures represent environment only and form no part of the claimed design.”

It made similar constructions for the other 3 patents in suit.

Score one for the patentee!

I will be speaking on The Future of Design Patent Law at the Intellectual Property Owners (IPO) Annual Meeting, which takes place online September 21-24, 2020. The exact day and time of my talk has not been finalized.

Statutory changes in the design patent laws (35 U.S.C. 171 et seq.) are long overdue. In fact, despite numerous statutory amendments to the general patent laws (35 U.S.C. 101 et seq.) there has been no change in the design patent laws in nearly 70 years, since the passage of the 1952 Patent Act. Such changes can address numerous gaps and deficiencies in the design patent laws, and update other sections of 35 U.S.C. (which were written for utility patents) to make it clear that design patents are governed under a separate legal regimen (as one example, the requirement in 35 U.S.C. 112 that a patent disclosure must teach one how to “make and use” a claimed invention makes no sense when it comes to aesthetic designs).

I will “introduce” legislation to address these gaps, deficiencies and inconsistencies, as well as improve the system for the benefit of users and the public. The proposed new laws will also correct some poor judicial decisions that have wreaked havoc both in design patent prosecution and enforcement.

More particularly, my talk, and the legislation, will address such issues as:

*protecting the design, rather than the article of manufacture to which it is applied (as is done in Europe)

*defining “ornamental”

*defining “functionality”

*introducing a new Sec. 112 for designs

*providing for multiple claims in a design patent

*clarifying permissible amendments to the drawings

*defining design patent anticipation under 35 U.S.C. 102 to effectively overturn International Seaway

*requiring consideration of the prior art in determining infringement

*updating 35 U.S.C. 289 re: total profit damages

*addressing miscellaneous issues such as inventorship, the manner of executing and amending drawings, the presence of logos/brands on the infringing product, and willful infringement.

It is believed that the virtual, online conference will draw from a large national and international audience, since travel expenses obviously need not be incurred. Don’t miss it.

The full program is here.

Several readers pointed out to me that the links to the two IPRs cited in yesterday’s post were inoperative. I know how excited you are to review those opinions (right?), so I’m correcting those links below:

I apologize for stuffing your in-box again, but at least one of these opinions are well-worth reading (they are substantially the same), especially if you’re a design patent law aficionado.

Perry Saidman

In an amazingly detailed and excellent analysis, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, in two 77-page opinions (IPR2017-00091 and IPR2017-00094) rejected Campbell Soup’s challenge of two Gamon, Inc. design patents (D621,645 and D612,646, prepared and prosecuted by yours truly). Also to be congratulated is Terry Johnson, president of Gamon, Inc. and the main inventor of the challenged patents, whose doggedness has paid off (well, he still needs to collect total profit damages from Campbell, see the last paragraph of this blog).

The PTAB effectively neutered the Federal Circuit’s previous, highly questionable opinion in Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon, Inc., 939 F.3d 1335 (2019), which I had previously written about in this space – see FEDERAL CIRCUIT KICKS THE CAMPBELL SOUP CAN DOWN THE ROAD.

Gamon’s two design patents were for the appearance of portions of a gravity-feed dispenser, specifically for soup cans. Both patents claimed the convex label area, and a cylindrical can at the bottom of the dispenser, ready for a consumer to take it. The two patents differed mainly in that the ‘646 patent claimed the “stops” or tabs that prevented a dispensed can from falling on the floor. The ‘645 patent did not claim the tabs. Since both decisions were in essence the same, I will refer to them as if they are one.

The main prior art reference relied upon by Campbell in its invalidity contentions based on obviousness was Linz (D405,622). Four secondary references were also relied upon.

GAMON U.S. Pat. No. D612.646

LINZ U.S. Pat. No. D405,622

In an earlier opinion, the PTAB in its obviousness analysis found Linz was not a proper primary or Rosen reference because, essentially, Linz did not disclose a can, and a can was claimed as part of Gamon’s design. The Federal Circuit on appeal was not impressed by the fact that Linz did not specifically disclose a can, and reversed the PTAB, saying: “Linz [was] for dispensing cans and … a can would be used in the system…. The parties do not dispute that Linz’s design is made to hold a cylindrical object in its display area.” There was a vigorous dissent by Judge Newman (who in my opinion knows design patent law better than her colleagues). She correctly stated: “… [T]he only claimed design elements are the label area and the cylindrical object ... the cylindrical object is a major design component. The absence from the primary reference of a major design component cannot be deemed insubstantial.” In my prior blog, I opined that the Court’s majority holding to be very disturbing, going against the weight of authority. The case was sent back to the PTAB, and the instant opinion resulted.

This time, the PTAB of course found that Linz was a proper Rosen reference, bowing to the Federal Circuit decision, as it must. And it also found that two secondary references were properly combined with Linz “to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.”

Normally, that would end the analysis and Gamon’s claim would be found invalid for being obvious to a designer of ordinary skill. But Gamon, smartly, introduced a ton of so-called “secondary considerations” that swung the pendulum in its favor, away from a finding of obviousness.

One had a sense of where the decision was headed after the Board devoted six pages early in its opinion to describing the development of the design by Terry Johnson. It was an impressive recap, noting how Campbell Soup, Gamon’s customer, had bought $31 million of the gravity feed dispensers (dubbed “IQ Maximizer”), placed them in 2,800 stores, and touted the design to investors in its 2005 Annual Report: “[t]he strong performance of Campbell’s condensed soup business demonstrates the value of the IQ Maximizer, an innovative gravity-feed shelf system for merchandising soup…. making the soup aisle dramatically easier for consumers to shop.” Campbell’s 2006 Annual Report described the IQ Maximizer as now “available in 16,000 stores… [it] continues to be a powerful tool to merchandize Campbell’s condensed soups.” Campbell described the IQ Maximizer as a “tool to deliver impactful consumer messages at the point of purchase …. [and is] a breakthrough in soup merchandising.” The Board concluded the history lesson by noting that in late 2008, Campbell began purchasing gravity feed display racks from Petitioner Trinity, the manufacturer of the infringing racks, that “maintained the same ornamental design features as the Gamon racks.” This was the genesis of the current dispute. Gamon has sued Campbell for infringement in federal court, which stayed the proceedings while Campbell challenged Gamon’s patents.

The Board tellingly began its analysis by considering the “final Graham factor – objective indicia of nonobviousness.” Graham, of course, refers to the Supreme Court’s seminal decision Graham v. John Deere, 383 U.S. 1 (1966) that laid out four factors that must be taken into account in determining nonobviousness: (1) the scope and content of the prior art; (2) the level of ordinary skill in the art; (3) the differences between the prior art and the claims at issue; and (4) secondary considerations. The latter factor, as stated by the Court in Graham, includes such things as commercial success, industry praise, copying by others, long felt need, and the like, that bear on whether the invention is nonobvious. The PTAB quoted the Federal Circuit from Apple v. Samsung:

“Indeed, evidence of secondary considerations may often be the most probative and cogent evidence in the record. It may often establish that an invention appearing to have been obvious in light of the prior art was not. It is to be considered as part of all the evidence, not just when the decision maker remains in doubt after reviewing the art.”

Significantly for Gamon, in connection with its anticipated recovery from Campbell of its total profit on sales (35 U.S.C. 289), the Board said that “Campbell’s internal documents and official public filings [are persuasive] that the claimed ornamental aspects of the commercial embodiment contributed to both the success of the sales of the display rack, and also to sales of soup cans displayed as part of the claimed design (emphasis added)”. This will factor into whether Gamon, in its suit against Campbell for infringement, can successfully claim Campbell’s total profit on sales of soup as damages under 35 U.S.C. 289, which will result in a very big number. Trinity, of course, will be liable to Gamon for its total profit on the sales of the dispensers, although it will have a “component” argument in view of the Supreme Court’s decision in Samsung v. Apple, which effectively allowed apportionment of total profit between a component of a product and the whole product.

The first hurdle for Gamon was to show the required “nexus” between the secondary considerations and the claimed design. A nexus is shown when there is a legally and factually sufficient connection between the evidence and the patented design. After taking into account that the most visible portions of the display rack when in use are the portions that are claimed, the Board concluded that the evidence of secondary considerations is the direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed design, and therefore established nexus.

In discussing the secondary considerations, the Board found that the evidence established that the commercial success of Gamon’s display rack and an appreciable amount of Campbell’s increased soup sales from 2002-2009 is attributable to the claimed ornamental features of the patented design: “The final record establishes persuasively that the claimed ornamental design features, specifically the pronounced label area resembling the side of a can, as well as the cylindrical can lying on its side underneath the label area, attracted customers to the gravity feed display and allowed them to efficiently find and purchase soup products.” The Board said that the display “jumped out” and attracted soup customers.

The Board also noted that the proportionality [of the label area] in the claimed design was original and created a display that looked like a soup can, which contributed to the success of the patented display rack and also to increased soup sales. The Board found that Gamon’s ornamental design turned the soup can on its side, and that, as another secondary consideration (disbelief in the industry), the record demonstrated that Campbell originally believed that setting the can on its side would not work in commercial use, which the Board concluded indicated the originality of the design.

Suffice it to say, the evidence of commercial success was overwhelming, and the Board’s opinion is significant for that reason. It is the only case of which I am aware where a design patent – that otherwise would have been found obvious in view of the prior art – was “rescued” by secondary considerations. Rather than reciting further details of the opinion, I highly commend it to your reading. The PTAB, once again, has demonstrated a keen grasp of design patent law.

What will happen next? Campbell can further delay judgment day by appealing this decision to the Federal Circuit, but the evidence of secondary considerations is so great that it would have a difficult time getting the Board’s decision on obviousness reversed. Or the parties can trundle back to the district court which will lift its stay so that the infringement case can proceed, with Campbell perhaps raising other defenses (non-infringement is a non-issue). Or Campbell, after reviewing its potential damages liability by calculating its total profit on soup sales during the period in question, may come to the table to negotiate with Gamon. But profit on soup sales is such a large number that a settlement - especially given Campbell’s propensity to litigate - may be difficult to reach. And both Campbell and Trinity have had a tendency in this dispute to throw every roadblock they can in front of Gamon and Terry Johnson. Campbell should keep in mind that the can is a major visual component of the claimed design (besides the label, the rest of the dispenser is disclaimed) such that it would have a hard time, in this author’s opinion, avoiding a final judgment that it is liable for its total profit on soup sales.

As I have written previously in this blog, Judge Lourie, writing for the Federal Circuit in the Columbia v. Serius case, put a dagger in the hearts of design patentees by saying, in essence, that a copycat defendant who otherwise infringes a patented design can potentially avoid liability simply by putting its logo on its product.

Unfortunately, the good judge has set back design patentees once again in Lanard Toys Limited v. Dolgencorp LLC, Ja-Ru, Inc., and Toys “R” Us-Delaware, Inc. (2019-1781, May 14, 2020) in allowing an admitted copycat to escape liability.

I. CLAIM CONSTRUCTION

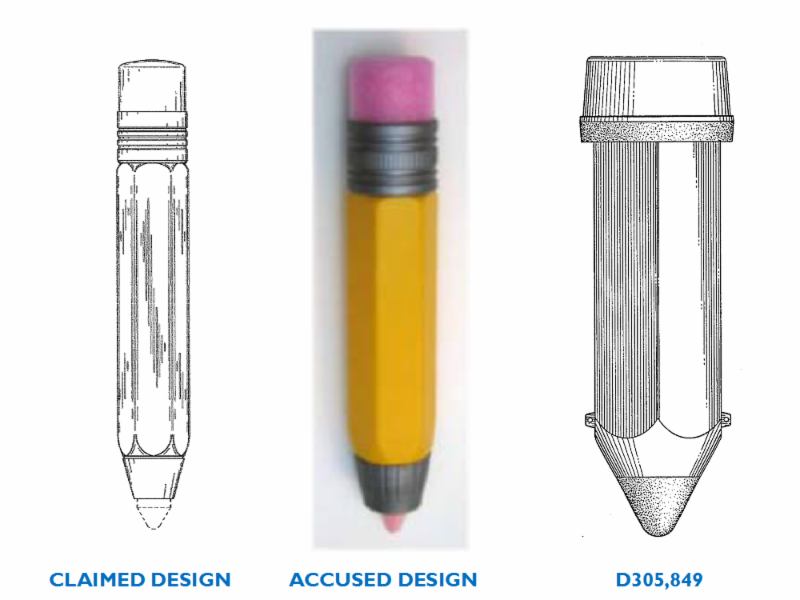

In Lanard, the claimed design (U.S. Pat. No. D671,167) is a toy chalk holder, as was the accused device, to wit:

The claim of Lanard’s ‘167 patent is what one would expect:

“The ornamental design for a chalk holder, as shown and described”.

Copying was admitted: “It is undisputed that [the defendant] used the [patentee’s design] as a reference in designing its product”. Slip op. at *3.

During claim construction, the district court considered Lanard’s argument that the recitation of a “chalk holder” in its claim was important, saying: “This construction of the claim is critical to Lanard’s patent infringement argument because it relies heavily on the chalk holder function of its design as the overriding point of similarity between the patented design and accused design that is absent from the prior art.” However, the court disagreed with Lanard’s argument:

“[T]o the extent that Lanard’s argument is that the court should consider the article of manufacture itself as an element of the design separate from its visual appearance, the court is not persuaded. Such an argument is inconsistent with the long-standing principle in design patent law that “[u]nlike an invention in a utility patent, a patented ornamental design has no use other than its visual appearance,” such that “its scope is ‘limited to what is shown in the application drawings.’”

To support the foregoing, the court basically said that the protected design is limited to what is shown in the drawings, and that the language of the claim and specification doesn’t matter.

Upon review of the district court’s claim construction, the Federal Circuit said:

“[T]he district court fleshed out and rejected Lanard’s attempt to distinguish its patent from the prior art by importing the “the chalk holder function of its design” into the construction of the claim. [W]e see no error in the district court’s approach to claim construction.” Id. at *13.

This conclusory treatment sidesteps an important issue in the case, namely whether the specific language in Lanard’s claim should be taken into account in determining infringement.

In brushing off this question, the Federal Circuit failed to consider its own precedent Curver v. Luxembourg from September, 2019. In Curver, the Court found that the title/claim of the design patent definitely mattered in determining infringement.

The patentee’s claim in Curver was: “The ornamental design for a pattern for a chair, as shown and described”, and the accused infringer used substantially the same pattern on a basket. In finding no infringement, the Court in its claim construction said that the word “chair” limited the scope of the design patent.

In the Lanard case, however, neither the district court nor the Federal Circuit gave any weight to the fact that the claimed design was for “a chalk holder”. The infringer made a chalk holder, but none of the prior art designs - none of them – was for a chalk holder.

This raises some interesting questions to ponder:

Should weight have been given to the fact that both the patentee and infringer made chalk holders, and the prior art reviewed by the district court - although rife with pencils and pencil-shaped objects – was devoid of chalk holders?

Should the prior art relevant to validity and infringement be limited to chalk holders, or extend to any object that looks similar to Lanard’s design?

If the prior art included a hand-held pastry dispenser that looked exactly like Lanard’s chalk holder, would that invalidate the patent?

Would a designer of toy chalk holders look to No. 2 pencils, beverage containers and/or pastry dispensers for inspiration in designing a new chalk holder?

What is the nature and scope of prior art that an ordinary observer should be aware of when considering whether a patented and accused design are substantially the same?

Would Lanard have a cause of action for infringement against someone who made a beverage dispenser that looked exactly like Lanard’s chalk holder?

II. INFRINGEMENT

The district court considered 8 pieces of presumed prior art, illustrations of which were included on p. 33 of its opinion. The court relied heavily on the No. 2 pencil as prior art (it was mentioned 41 times in its opinion), even though Lanard’s design was clearly shorter and stubbier than a No. 2 pencil.

Lanard’s Claimed Design

In its review of the district court’s summary finding of no infringement, the Federal Circuit quoted the lower court with approval:

“The district court thus recognized that “the overall appearance of Lanard’s design is distinct from this prior art only in the precise proportions of its various elements in relation to each other, the size and ornamentation of the ferrule, and the particular size and shape of the conical tapered end.” “

Differences in proportion, size, shape & ornamentation between the patented design and the prior art are important considerations in determining infringement – especially if the accused design shares similar differences with the prior art, as is arguably the case here. In other words, given the differences between the claimed design and the prior art, and given the fact that similar differences with the prior art are also found in the accused design, does this not support the position that the patented and accused designs may be closer to each other than either is to the prior art, which would make out a decent case for infringement?

Under these circumstances, could not a reasonable jury find infringement? Was summary judgment, reserved for cases where no reasonable jury could find infringement, appropriate here?

Interestingly, regarding the summary judgment issue, Judge Lourie dissented (without opinion) in the very recent Spigen v. Ultraproof case where the Court reversed a lower court’s grant of summary judgment of obviousness, saying that a reasonable jury could indeed find the claimed design non-obvious. Does this suggest a trend to affirm summary judgments that take the teeth out of design patents? Hopefully not.

Before the district court, Lanard relied on similar proportions of the patented and accused designs to establish infringement. The district court rejected this, saying that the relative size and thickness of the designs as compared to No. 2 pencils is a "functional modification necessary to accomplish the chalk holder function of the devices". This seems tantamount to the court saying that yes, they look different, but only because you designed a chalk holder and not a pencil.

Let’s delve deeper into the actual facts of this case, something the Federal Circuit apparently declined to do.

The district court said that "the overall proportions of the patented design are similar to the [prior art] Giant Pencil as they are to the accused design". However, upon comparing the proportions of the designs, the Giant Pencil (shown below) has an aspect ratio (length to diameter) close to 10, while that of the claimed design is around 7, and that of the accused design is close to 5.

Another prior art reference of record, the Insulating Container of U.S. Pat. No. D305,849, has an aspect ratio of about 5, making its proportions more similar to the claimed design and accused design than the Giant Pencil. A comparison of the claimed design, the accused design, and seemingly the closest prior art (the '849 patent) is instructive:

One can easily appreciate that the accused design is closer in appearance to the claimed design than either is to the closest prior art, i.e., the '849 patent. This makes a finding of infringement more likely than not, despite the minor differences between the patented and accused designs. Once again, one must ask whether a reasonable jury could find infringement; if so, summary judgment of non-infringement should have been denied.

It is interesting to note that despite numerous general references to “the prior art”, the Federal Circuit’s opinion is devoid of any illustrations or factual discussion of specific prior art, which seems at odds with its Rule 56 obligation (“In the Eleventh Circuit, a grant of summary judgment is reviewed de novo, ‘construing the facts and all reasonable inferences from the facts in favor of the nonmoving party’” (citations omitted), Slip op. at 4). In other words, if the foregoing facts about the prior art, and reasonable inferences drawn therefrom, are all viewed in favor of Lanard, summary judgment against it would seem inappropriate.

III. WAIT, THERE’S MORE!

The capper in the Court’s opinion came when it said:

“We ultimately conclude that Lanard’s position is untenable because it seeks to exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil and thus extend the scope of the D167 patent far beyond the statutorily protected “new, original and ornamental design.” 35 U.S.C. § 171.”

Nowhere did Lanard seek to exclude any chalk holder in the shape of a pencil. It is an absurd position. Lanard only sought to exclude a chalk holder in the shape of a pencil that was substantially the same in overall appearance as its patented design.

Another gaffe worthy of mention is the Court’s treatment of functionality. It resurrected the discredited Richardson v. Stanley Works logic when it cited the Amini v. Anthony case for the proposition that during claim construction a district court must “factor out the functional aspects of various design elements”. This very Court has put this misguided statement to bed in the Ethicon v. Covidien and Sport Dimension v. Coleman cases that essentially found that every utilitarian feature – every one – has an associated appearance, and it is that appearance that is taken into account in determining infringement. Nothing is to be “factored out”. This goes for utilitarian features and “old” features. For example, if a design patent for some reason claims old features, i.e., features that are in the prior art, the scope of the claim will include the appearance of those features. The appearance of claimed utilitarian features are similarly not ignored. If the patentee wants to disclaim the appearance of old or utilitarian features, they should put such features into broken lines, as any design patent practitioner knows.

Sometimes it is interesting to think about what might happen if the accused design were prior art...

Musing #1: Could the claimed chalk holder have been found obvious in view of the prior art of record? In order to be held obvious, a single reference – called the “primary reference” - must be found that is “basically the same” in appearance as the claimed design. Are any of the cited prior art references basically the same as the claimed design? Under the prevailing legal standard, probably not. Would the accused design qualify as a primary reference if it were prior art? Probably.

Why is this relevant? Because the standard for infringement is whether the two designs are “substantially the same” which is virtually indistinguishable from the standard for a primary reference - “basically the same”. So, if the accused design constitutes a valid primary reference against the claimed design if it were prior art, then it also infringes the claimed design. This logic is buttressed by the requirement that obviousness is judged through the eyes of a designer skilled in the art, while infringement is judged through the eyes of an ordinary observer. The latter’s visual acuity is presumably lower than the former’s. So if a person with a greater sense of observation, i.e., a designer, finds a reference to be basically the same as the claimed design, then a person with a lesser degree of observation, i.e., an ordinary observer, could easily come to the conclusion that such designs are substantially the same.

Musing #2: Would a USPTO examiner find that the accused design – if it were prior art – anticipates the claimed design under section 102? Probably. In so doing, the examiner would apply the “ordinary observer” test which, under International Seaway*, is now the test for anticipation as well as infringement. Thus, if the accused design anticipates the claimed design, it must also infringe it.

*As I have pointed out on many occasions, including my recent paper, the International Seaway decision is deeply flawed. However unfortunate, it is still the law.

In a case that is extraordinarily ordinary - Spigen Korea Co., Ltd., v. Ultraproof, Inc., et al - the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on April 17, 2020 reversed the lower court’s finding that 3 of Spigen’s design patents on a cover for a mobile phone (D771, 607; D775, 620; and D776,648) were obvious as a matter of law.

It’s too bad that the Spigen decision didn’t come down a few weeks earlier, so that the district court in another summary judgment case involving obviousness of sausage packages – Johnsonville Sausage LLC v. Klement Sausage Co Inc. (E.D. Wisc., 16-C-938, 3/27/2020) – could take its lesson to heart.

The district court in Spigen found that U.S. Pat. No. D729,218 was a proper primary reference and invalidated Spigen’s patents on summary judgment (the secondary reference D772,209 was immaterial to the decision). The Federal Circuit found that a reasonable jury could have found that the ‘218 reference was not a proper primary reference, and therefore reversed on that ground. Note that the Court did not decide that the ‘218 reference was or was not a proper primary reference, only that a reasonable jury could find either way and therefore the question was inappropriate for disposition on summary judgment. The Court used the following illustration in its opinion to compare the ‘607 design with the ‘218 design:

It is black letter law that in order to find a design patent obvious, there must be a single prior art reference – a something in existence – that is “basically the same” in appearance as the claimed design to a designer of ordinary skill. The Federal Circuit reviewed the district court record to note similarities and differences between the ‘607 claimed design and the purported primary reference - the ‘218 patent.

For example, with respect to the ‘607 design the patentee Spigen argued that the ‘218 design was deficient in that it lacked an outer shell that wraps around the back and side surfaces, lateral parting lines, and a large circular aperture on the rear surface. Also, it argued that the ‘218 design’s side surfaces and chamfers were too large, and had ornamental triangular elements on its front surface. Ultraproof advanced counterarguments.

In view of the competing evidence introduced by Spigen and Ultraproof as to whether the ‘218 design was basically the same as the ‘607 design, and because a reasonable jury could find either way, the Court reversed the lower court’s summary conclusion that it was.

There were two mildly interesting parts of this decision. First, the Court did not compare the ‘218 patent – the alleged primary reference – with the other two Spigen design patents, the ‘620 and ‘648 patents. This is significant because the latter two patents disclaimed many of the features that were claimed in the ‘607 patent. Thus, it is possible that the ‘218 patent is a proper primary reference against the plaintiff’s two broader patents.

As seen above, the ‘648 patent disclaimed the prominent, large circular aperture on the rear face of the cover – a feature that had been argued to be absent from the alleged primary reference. Thus, it would seem that the Court’s opinion may have been different had it compared the alleged primary reference to Spigen’s broadest design claim (the ‘648 patent) rather than only to the narrowest (the ‘607 patent).

The second curious thing about this decision was that Judge Lourie dissented, without opinion. We therefore do not know what he disagreed with; perhaps it was the basic finding that the ‘218 patent was not a proper primary reference. Note that Judge Lourie also wrote the opinion in the earlier Columbia v. Seirus design patent case, one having a very questionable finding that the infringer’s logos on its product should be taken into account in determining infringement (see my earlier blog post).

Turning to the Johnsonville case, the district court similarly granted the defendant’s motion for summary judgment that the plaintiff’s claimed design for a sausage tray, U.S. Pat. No. D633,754, was invalid based on obviousness in view of U.S. Pat. No. 3,761,011 as the purported primary reference, and U.S. Pat. No. D198,544 as the secondary reference (the ‘544 secondary reference is not material to this discussion). The ‘754 claimed design (FIGS. 7 & 8) and the ‘011 tray (FIGS. 1 & 2) are shown below:

‘754 CLAIMED DESIGN

‘011 PRIMARY REFERENCE

Note first that the ‘754 patent asserted by the plaintiff claimed only the curved end walls of the tray – every other element was shown in broken lines. The district court regarded the ‘011 patent as “a straightforward primary reference”. The ‘011 patent illustrates what the court correctly characterized as “a generic food tray”. The court believed that both the ‘754 end walls and those of the ‘011 patent created “the same visual impression as the ratio of the depth, width and spacing of the end walls in the claimed design”. The court astutely noted that the “only visual difference” between the two was that the end walls were curved in the patented design and straight in the purported primary reference. Then - somewhat astonishingly - it relied on “the striking similarity” between the generic ‘011 design and the generic rectangular sausage tray that Johnsonville used before it adopted the ‘754 design to “reinforce” its conclusion that the ‘011 patent is an appropriate primary reference.

It used to be black letter law that a purported primary reference that is missing a significant visual feature of the claimed design could not be a proper primary reference. However, the Federal Circuit’s recent Campbell Soup case – not cited by the district court here - found to the contrary in that the primary reference there was missing a significant visual element of the claimed design – a can – but the Court nevertheless found the reference to be a proper primary reference, (cf. the persuasive dissent by Judge Newman); see my earlier blog post.

Perhaps on appeal the Johnsonville case would be decided differently than was the Campbell case, because in the former, the curved end walls were not simply a significant visual feature, but virtually the only significant visual feature, whereas in the latter the can was but one of three significant visual features.

Similar to the Spigen decision, it would seem that at the very least, the Johnsonville case was not one to be disposed of on summary judgment, since the question of whether the ‘011 patent was a proper primary reference is reasonably in doubt and thus triable to a jury. Thus, if appealed, the Johnsonville case would seem to stand a reasonably good chance of being reversed and remanded.

Perry Saidman will be a speaker at the UT LAW/CLE event: 15th Annual Advanced Patent Law Institute to be held March 12-13, 2020 at the United States Patent and Trademark Office in Alexandria Virginia.

Perry’s talk is scheduled for Thursday afternoon, March 12th, and is entitled: “Potpourri of Hot Design Patent Issues: Practical Implications”. He will touch on a wide range of subjects including: maximizing total profit damages in the wake of Samsung v. Apple; choosing an effective title/claim for your design patent application; protecting fashion with design patents and copyrights; and what to do when the Federal Circuit kicks the can down the road: the ramifications of Campbell v. Gamon.

The Institute is co-sponsored by The University of Texas School of Law and The George Mason University Antonin Scalia Law School. Program details and registration information can be found here.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s 2009 decision of International Seaway v. Walgreens held that the ordinary observer design patent infringement test is the sole test for anticipation under 35 U.S.C. 102.

International Seaway drastically changed the well-settled law of design patent anticipation from a relatively objective standard (the prior art must be identical to the claimed design) to a very subjective one (the prior art must only be substantially the same as the claimed design). This change in the law was ill-considered.

My paper examines the underpinnings of the Seaway case, in the hope that a case will soon present itself to the Federal Circuit so that the test for design patent anticipation can be returned to its correct original formulation.

On November 13, 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down its opinion in Columbia v. Seirus that involved a design patent on a 3-D pattern of a heat reflective material. The appeal was focused on the identification of the “article of manufacture” of the accused design upon which total profit damages would be assessed for the successful design patentee Columbia.

The Federal Circuit dodged the issue of damages, and reversed the lower court’s summary judgment holding. Among other things, the Court found that the lower court had failed to take into account the infringer’s placement of its logo on the accused design, saying that the jury should have been able to take that into account in determining whether the accused design was substantially the same visually as the patented design. Such a finding, if undisturbed, would be a disaster for design patent holders, as explained in my previous post.

Columbia has petitioned for rehearing based in part on the court’s logo finding. A number of amicus curiae briefs were filed in support of the Court either granting rehearing on the logo issue, or at least clarifying that portion of its opinion.

One such amicus brief was filed by a Group of Interested Practitioners, seven design patent lawyers of whom I was one. Another amicus brief was filed in the name of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), and a third in the name of Bison Designs and Golight, two companies actively engaged in design patent procurement and enforcement.

Such petitions for rehearing unfortunately have only a small chance of being granted, so clarification/correction of this issue may well need to wait for another case. I will keep you updated on the progress of this appeal as it unfolds before the Federal Circuit.

I am pleased to announce that I will be speaking in an upcoming Strafford live webinar, "Design Patent Enforcement: Recent Case Law Decisions and Trends, Due Diligence Considerations, and Best Practices" scheduled for Tuesday, February 18, 1:00 pm-2:30 pm EST.

For enforcement of design patents, there are certain best practices that will aid in successful enforcements and minimize pitfalls. Some of these issues include due diligence strategies, policing rights, seeking the appropriate level of engagement, and recognizing the realistic and appropriate scope of design patents. If a lawsuit is necessary, knowing who, where, and how to bring a lawsuit may be critical. Knowing the risks of initialing a lawsuit should also be considered.

Successful enforcement also requires the understanding and appreciation of data surrounding the results of recent design patent litigation. Recent case law decisions may also be critical as decisions relating to the scope of a design patent claim, and defenses such as obviousness and indefiniteness should be considered.

Additionally, strategies for litigation also affect remedies and damages. Best practices also impact whether meaningful monetary or injunctive relief is granted. This can be particularly difficult in view of the state of flux of the tests being applied for infringer’s profits.

Our panel will guide patent counsel on the enforcement of design patent rights. The panel will examine the key considerations involved in determining whether to sue when there is an alleged infringement. The panel will also discuss recent design patent enforcement trends and offer guidance for enforcement and on avoiding common mistakes when enforcing design patent rights.

We will review these and other high profile issues:

What factors should counsel consider when determining whether a design patent has been infringed and whether, where and when to file suit?

What steps should counsel take to avoid common mistakes when enforcing design patent rights?

What strategies can counsel use for effective enforcement of design patent rights?

After our presentations, we will engage in a live question and answer session with participants so we can answer your questions about these important issues directly.

I hope you'll join us.

For more information or to register.

Or call 1-800-926-7926

Ask for Design Patent Enforcement on 2/18/2020

Mention code: PL1V21-89OJAY

Sincerely,

Perry Saidman, Of Counsel

Saidman Design Law Group

Silver Spring, Md.

In Simpson Strong-Tie Company v. Oz-Post International (dba OZCO Building Products), (2019 WL 6036705, N.D. Cal., November 14, 2019), the district court found that Simpson’s accused design did not infringe OZCO’s U.S. Pat. No. D798,701. Shown below are two figures from the ‘701 patent next to two views of the alleged infringing design (the court’s figures shown below erroneously identify OZCO’s patent as the ‘901 patent).

In analyzing infringement, the judge found that “No reasonable juror could find that a consumer might be deceived into purchasing the Accused Products believing them to be the patented design.” It was conceded by the patentee OZCO that its patented design did not include the screw shaft. There were other relatively minor differences between the patented design and the accused products.

OZCO argued that the screw shaft is a purely functional feature and should be disregarded in determining infringement. The court said that “courts ignore functional features not of accused products but instead of the patented design”, curiously citing the Federal Circuit’s Coleman v. Sport Dimension decision which actually said just the opposite, i.e., that functional features should be considered insofar as they contribute to the design’s overall ornamentation.

The court then said that the screw distinguished the accused product from the patented design, saying “It would be impossible for an ordinary observer to miss the presence of the screw…” Remarkably, it then stated that Simpson’s screw was sold separately from the hex head washer – a fact that should have ended the discussion about whether the screw was a distinguishing feature.

The major error of the court was its finding that the presence of the screw in the accused products mattered in infringement analysis. Federal Circuit precedent holds otherwise. For example, in Advantek v. Orion, a 2018 decision, the patentee asserted its design patent D715,006 for a Gazebo against the defendant’s Pet Companion Product. The two designs are shown side-by-side below.

Although the major issue in Advantek was prosecution history estoppel, the argument was raised by the defendant that their product was sold with a cover, whereas the patented design did not include a cover. This is directly analogous to the situation in Simpson v. OZCO. The Federal Circuit, in a precedential decision, said:

Advantek elected to patent the ornamental design for a kennel with a particular skeletal structure. A competitor who sells a kennel embodying Advantek’s patented structural design infringes the D’006 patent, regardless of extra features, such as a cover, that the competitor might add to its kennel.

If infringers could escape liability by simply hanging an extra element onto the accused product, design patents would become irretrievably useless.

The “Counterfeit Goods Seizure Act of 2019” was introduced in the U.S. Senate to empower U.S. Customs and Border Protection to enforce U.S. design patents at the U.S. border.

Currently, U.S. laws empower Customs to enforce copyrights and trademarks that have been previously recorded with Customs. The proposed legislation will give Customs similar discretionary power to seize and detain imported goods that infringe a recorded U.S. design patent. The bill is publicly supported by Nike Inc. and the 3M Company, as well as many other American companies, the International Trademark Association (INTA), the Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO) and the American Intellectual Property Owners Association (AIPLA).

Currently, the only way to enforce a design patent at the U.S. border is for the owner to undertake a long and expensive process at the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) under Sec. 337 of the Tariff Act. Although Sec. 337 was originally designed to adjudicate much more complex, technology-based utility patents, design patents must go through the same process because – by historical accident – design and utility patents are governed by the same statute, Title 35 of the U.S. Code. Advocates of the new bill point out, however, that design patents, which protect the appearance of a product, are much more akin to copyrights and trademarks than to utility patents, and that copyrights and trademarks do not have to go through the ITC in order to be enforced at the border. The bill is an attempt to correct this dichotomy.

Counterfeiters have become very clever. Knock-off manufacturers and sellers have recognized that counterfeit products (which bear infringing trademarks) are potentially at-risk to seizure by Customs, but the very same products not bearing the infringing trademarks generally evade seizure. In 2018, a group of counterfeiters was arrested who had imported over $70 million in fake Nike shoes by omitting labels to evade Customs officials; the labels were attached after importation. Amending the law to empower Customs to enforce design patents would go a long way towards plugging these and similar loopholes.

Counterfeit products may pose serious consumer safety concerns. For example, counterfeit consumer electronics (e.g., power adapters, chargers, and devices) may fail or overheat leading to fire and electrocution risks. Counterfeit automotive parts (e.g., wheels, headlights, and windshields) often have higher failure and malfunction rates than genuine parts.

The infringement test for design patents was simplified in 2008 in the landmark case of Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, which will make it easier for Customs officials to evaluate infringement of a design patent. Customs officers would only have to determine whether the patented design and the suspect imported design are substantially the same in overall appearance. This analysis is similar to the analysis currently undertaken by Customs in cases of suspected trademark infringement. Customs officers have already effectively demonstrated the ability to determine whether imported goods infringe a design patent, through its ongoing enforcement of design-patent exclusion orders that are issued at the successful end of an ITC proceeding. But, as the amendment is currently drafted, in the event Customs is unable to concretely determine a violation, the agency would have the discretion not to seize the goods, because, as with violations of copyright and trademark, CBP’s authority to seize is discretionary (e.g., “The merchandise may be seized and forfeited if . . . .”).

If the bill is enacted, the United States will join other modern IP design rights border enforcement mechanisms used by many other countries including the EU, Japan, South Korea, China, India, Mexico, Turkey, Argentina, South Africa, Switzerland, and Panama.

Clearly, this legislation is long overdue, and would be a boon to the U.S. economy. If you and/or your company favors enactment of this law, letters to your state’s House and Senate members would go a long way towards its enactment. Following is a sample letter that can be used as a template:

Dear Congressman/Senator (fill in):

[name of company], headquartered in [city, state]. We design, engineer, manufacture and sell worldwide [name types of products]. Our largest market is in the U.S.

[name of company] prides itself on, among other things, our iconic designs and our cutting-edge technology. We are the owner of substantial intellectual property including many design and utility patents, and we work hard to create, maintain and protect our brand, our market and our innovative technology in a highly competitive industry. U.S. design patents are a key component of our IP portfolio.

I want to express our company’s wholehearted support for the “Counterfeit Goods Seizure Act of 2019.” We have had a number of issues with foreign manufacturers of knock-off [name types of products] shipping them into the US, and passage of this bill would be an enormous help in stopping those counterfeits from flooding the market and adversely affecting our business.

We urge prompt passage of this bill, without reservation.

Very truly yours,

In Columbia Sportswear v. Seirus Innovative Accessories (No. 2018-1329, 2018-1331 and 2018-1728) (November 13, 2019), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit declined to decide the single most important and unresolved issue in design patent law: determining the “article of manufacture” upon which the infringer’s total profit is calculated under 35 U.S.C. Sec. 289.

BACKGROUND: The Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Samsung v. Apple held that the article of manufacture upon which the infringer’s total profit is to be calculated can be either the end product sold by the infringer, or a component of the end product. It did not, however, provide any guidance to the lower courts as to how the article of manufacture is to be determined in any given case. Three years have passed since the Supreme Court’s pronouncement. This is the first case to reach the Federal Circuit on this admittedly difficult issue.

Columbia’s design patent, D657,093, claimed a heat reflective material, and included drawings that showed this material applied to several end products, such as socks and gloves (the end products – socks & gloves - were shown in broken lines, i.e., disclaimed):

Columbia’s U.S. Pat. No. 657,093

Columbia’s U.S. Pat. No. D657,093

Columbia, of course, wanted the end products, e.g., socks and gloves, to be the articles of manufacture, simply because the total profit on those end products would be far larger than the total profit on the material alone. Naturally, the infringer Seirus wanted the material alone to be the article of manufacture, which would minimize the total profit. The jury awarded Columbia $3 million in total profit damages and the infringer Seirus appealed.

The urgent issue before the Federal Circuit was to determine the relevant article of manufacture, and in the process fashion an appropriate set of factors that a court should consider. The Columbia case was supposed to be the case where the Federal Circuit would finally give the lower courts – and litigants – guidance on this critical issue.

The Federal Circuit punted, kicked the can down the road - again! (see earlier post re: Campbell Soup case).

LOCO: Instead of wrestling with the article of manufacture gorilla, the court strained to reverse the district court’s grant of summary judgment of infringement and remanded the case.

In so doing, the court – rather remarkably, and unfortunately – said that the infringer’s logo on its products is a factor that must be considered in determining infringement. This is a startling ruling that will ultimately weaken design patents. It handed infringers a new, powerful weapon: simply include their logo/name on their infringing products.

Following are enlargements showing the infringer’s logo on two of its products:

In discussing this issue, the court tried to distinguish the venerable (and precedential) L.A. Gear case, (L.A. Gear, Inc. v. Thom McAn Shoe Co., 988 F.2d 1117 (Fed. Cir. 1993)). The court, citing L.A. Gear, said: “A would-be infringer should not escape liability for design patent infringement if a design is copied but labeled with its name.” But a few sentences later, it inexplicably said that the trier of fact cannot “ignore elements of the accused design entirely, simply because those elements included the name of the defendant”. How does one reconcile these two statements?

Those of us in the real world know that infringers are clever. Many copy exactly (or very closely) a design patented product, and put their own logo on it. Take footwear as an example: Nike shoes have their famous swoosh on every sneaker. Of course, Nike’s design patents do not claim the swoosh, because it would significantly narrow their scope.

After the Federal Circuit’s ruling in Columbia, an infringer is now incentivized to copy a patented design and try to avoid infringement by using, e.g., the word “balloons” on the side of its shoes, as did the infringer in L.A. Gear:

L.A. Gear’s design patent

Infringing “balloons” Design

In fact, it is a rather common practice. The infringers generally avoid putting the patentee’s name/logo on their product, because to do so would amount to counterfeiting which carries severe criminal penalties.

The presence of a logo/name significantly weakens the patentee’s case for infringement, because obviously the logo – any logo or name – is not going to be part of the patentee’s claimed design. Requiring courts to consider the overall appearance of the design including the logo by definition will make it more difficult for a design patentee to get an infringement ruling, for the logo will provide another visual element that the infringer can use to argue that its design is not substantially the same in overall appearance as the patented design.

OTHER FALLOUT: The court further chastised the district court for its “piecemeal approach” in that it spoke of individual design elements during its comparison of the patented design and accused products. The Federal Circuit said that: “the fact-finder must analyze the design as a whole”. But, as a practical matter, how does one analyze the design as a whole except by comparing individual elements of the design?

The Federal Circuit also criticized the district court for violating Rule 56 (Summary Judgment) in that it did fact-finding in the course of granting summary judgment. But district courts on summary judgment make findings of fact all the time, otherwise such motions would never be granted. The real question is whether the non-movant (infringer) introduced sufficient evidence - not simply a list of facts in dispute - such that a reasonable jury could find in its favor. The whole idea of summary judgment is to avoid potentially wasteful jury trials where there’s no triable issue of fact. The Federal Circuit glossed over this nicety.

UPSHOT: The Federal Circuit’s entire opinion regarding the design patent practically mandates another jury trial – hoping perhaps that the parties will now settle and postpone the necessity of the court to wrestle with the admittedly difficult – but extremely important – article of manufacture issue.

In Campbell Soup Co. et al. v. Gamon Plus, Inc, (2018-2029, 2018-2030, September 26, 2019), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ignored the absence of a major visual element in a claimed design by finding that a prior art reference - that lacked this element - was nevertheless a proper primary reference under 35 USC 103.

The design patent in question, U.S. Pat. No. D612,646, claimed a portion of a can dispenser, namely a label area above a cylindrical can having flat vertical tabs in front of the can. The sole figure is shown below:

GAMON’S PATENTED DESIGN

Following is the Linz primary reference:

LINZ PRIMARY REFERENCE

The test for a proper primary reference in design patent obviousness analysis is whether the reference’s overall visual appearance is “basically the same” as the claimed design. This goes back to the Court’s seminal case, Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996).

The most basic legal analysis – and logic - is that Linz cannot be basically the same in appearance as the ‘646 design if it is missing a claimed major visual element.

The Federal Circuit came to its conclusion with the flimsiest of logic:

“Accepting the Board’s description of the claimed designs as correct, the ever-so-slight differences in design, in light of the overall similarities, do not properly lead to the result that Linz is not “a single reference that creates ‘basically the same’ visual impression” as the claimed design. The parties do not dispute that Linz’s design is made to hold a cylindrical object in its display area.” [emphasis added]

Interestingly, neither the majority nor the dissent nor the Board discuss the claimed flat, vertical tabs that rest adjacent the cylindrical object. Linz shows curved tabs. Since only 3 elements are claimed in the ‘646 patent, the flat, vertical tabs certainly qualify as another major visual element.

Because of Gamon’s admission during oral argument that Linz’s dispenser was for a can, the Court used its imagination and imputed the appearance of a can into the Linz reference, and reversed the Board’s finding that Linz was not a proper primary reference.

To understand how ridiculous the Court’s holding is, imagine the hypothetical situation where Linz’s product appeared on the market after Gamon’s patent issued. Gamon sues Linz for infringement. The test for infringement is whether the designs are “substantially the same” in overall appearance, which is eerily similar to the test for a primary reference: whether it is “basically the same” as the claimed design. So, if Linz is a proper primary reference, it follows that the Linz product would infringe the Gamon patent – and I am 100% sure that no court in the land - much less a jury - would ever come to that conclusion.

Judge Newman in her dissent had it exactly right:

“My colleagues propose that since “Linz’s design is made to hold a cylindrical object in its display area”, the Linz design must be viewed with judicial insertion of the missing cylindrical element. This analysis is not in accordance with design patent law. Only after a primary reference is found for the design as a whole, is it appropriate to consider whether the reference design may be modified with other features, selected to match the patented design”. (emphasis added)

Ironically, in the seminal Durling case (citation above), the Court found the prior art reference to Schweiger was deficient as a proper primary reference precisely because it failed to disclose a significant visual element of the claimed design. The images of the patented design (top image) and Schweiger (bottom image) follow:

The Federal Circuit found that the absence of a triangular corner table in Schweiger prevented it from creating “basically the same visual impression as does Durling's design, and therefore cannot suffice as a primary reference.”

The Federal Circuit also contradicted the Board’s established precedent.

For example, in Vitro Packaging, LLC v. Saverglass, Inc., 2015 WL 5766302 (Sept. 29, 2015), the prior art bottle was deemed an improper primary reference despite having all the major visual elements of the claimed design.

CLAIMED DESIGN

ALLEGED PRIMARY REFERENCE