As is plain as day, the Linz patent lacks a primary claimed feature: the cylindrical can. Nevertheless, in an earlier opinion, the Court presumed the presence of a can in Linz (see another earlier blog) This was clearly a distortion of the law of non-obviousness, as set forth in Judge Newman’s cogent dissent.

But I digress. In the present case, the Board of course felt obligated to follow the Court’s misbegotten logic in its earlier opinion and found the claimed design obvious over Linz. As noted above, Gamon presented compelling evidence of secondary considerations; namely, commercial success and copying. It was so overwhelming that the Board found the two design patents nonobvious, even in view of Linz. This appeal followed.

Evidence of secondary considerations must have a “nexus” to the commercial product, i.e., the IQ Maximizer. That is, there must be “a legally and factually sufficient connection between the evidence and the patented invention”.

Nexus can be found to be “presumed”, or “in fact”. The Court addressed these issues separately.

a. presumed nexus

Relying on Fox Factory, Inc. v. Sram, LLC, the Court said: “As first recognized in Demaco Corp. v. F. Von Langsdorff Licensing Ltd., a presumption of nexus exists between the asserted evidence of secondary considerations and a patent claim if the patentee shows that the asserted evidence is tied to a specific product and that the product is the invention disclosed and claimed (emphasis in original). Conversely, [w]hen the thing that is commercially successful is not coextensive with the patented invention – for example, if the patented invention is only a component of a commercially successful machine or process,” the patentee is not entitled to a presumption of nexus, citing Demaco.

But the latter quote from Demaco was dicta, since the claimed invention in that utility patent case was a unitary paver stone, not a component of a machine or process. Design patents were not at issue.

Moreover, the Demaco court gave an example from the utility patent case Hughes Tool v. Dresser that held that “such continuous use of the patented feature while other features were not copied gives rise to an inference that there is a nexus between the patented feature and the commercial success.” In Gamon, the unclaimed side portions were not copied, only the front-facing portions of the label area, the can, and the tabs. So Demaco seems to support Gamon.

Also, the Demaco court relied on Railroad Dynamics, Inc. v. A. Stucki Co. that said: “The testimony as to the advantage of the spaced structure with the biasing spring easily supports the inference that the claimed invention itself was responsible for the commercial success”, a statement that if anything supports Gamon.

Thus, the Court’s reliance on Fox Factory was at best shaky.

b. nexus-in-fact

The Court stated that: “A patentee may establish nexus absent the presumption by showing that the objective indicia [of secondary considerations] are the ‘direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention”, citing in support In re Huang and Ormco Corp. v. Align Technology, Inc.

The Court interpreted the unique characteristics to mean the features that distinguish the claimed design from the prior art.

The Court’s decision regarding nexus-in-fact rested on its finding that the label element – what they deemed to be the only factor in the evidence of commercial success – was in Linz, the prior art. But the other two elements were absent: the can, and the vertical rectangular tabs (Linz’s tabs are rounded). The Court thus deconstructed the claimed design by ignoring the other two elements.

Indeed, what are the unique characteristics of Gamon’s claimed design? The answer is, of course, the features that were patented – the combination of the label area, the can, and the tabs. However, the Court focused only on the label area rather than the claimed combination.

Moreover, Huang actually said: “[commercial] success is relevant in the obviousness context only if there is proof that the sales were a direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention – as opposed to other economic and commercial factors unrelated to the quality of the patented subject matter”. In Gamon, there was no evidence of “other economic and commercial factors”, so Huang is not on point.

In Ormco, the Court said “[I]f the commercial success is due to an unclaimed feature of the device, the commercial success is irrelevant.” In Gamon, it can hardly be argued that the appearance of the unclaimed features resulted in the commercial success. There was no showing that the appearance of the unclaimed side portions of the IQ Maximizer had any impact on commercial success; in fact, it was just the opposite. It was the front facing portions, i.e., the label area, the can and the tabs that consumers saw and caused them to gravitate towards the product.

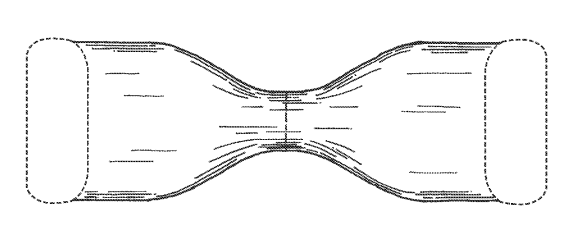

The Court found Gamon’s commercial success evidence was not directed to the can or the tabs; only the label area, finding that the latter was in the prior art to Linz. However, the Board, in its extensive review of this evidence, had concluded that: “The final record establishes persuasively that the claimed ornamental design features, specifically the pronounced label area resembling the side of a can, as well as the cylindrical can lying on its side underneath the label area, attracted customers to the gravity feed display and allowed them to efficiently find and purchase soup products.” The Board also cited the testimony of the inventor Terry Johnson, who explained that putting the can on its side was important and “what the consumer saw because there was a big convex sign that was the same as the label and it was in the same proportions as the can.” The Board had concluded: “The evidence shows that this proportionality in the claimed design was original and created a display that looked like a soup can, which contributed to the success of the patented display rack and also to increased soup can sales.” The Court dismissed Johnson’s testimony as “self-serving”, but cited no evidence to the contrary.

In response to Gamon’s evidence that the label area displays soup labels printed twice their normal size, the Court said that “the claimed designs do not require any specific size of the label area…because the patents’ figures depict the label area boundaries using broken lines… the size of the label area is not claimed.” Clearly, even though the boundaries themselves are disclaimed, all of the surface area between the boundaries is claimed (yet another example of the Court’s fundamental misunderstanding of design patents). Thus, the size of the label area, and the fact that it’s about twice the size of the soup label, is readily discernable.

c. Copying

In the Court’s penultimate paragraph, it chose to ignore copying of the patented design by Trinity, saying:

“[W]e assume substantial evidence supports the Board’s finding that Trinity copied the unique characteristics of the claimed designs. Even accepting the evidence of copying, we conclude that this alone does not overcome the strong evidence of obviousness that Linz provides.”

This is astonishing. There’s no reason that evidence of commercial success trumps evidence of copying. The Court gave none. Instead, it dismisses evidence of this particular secondary consideration in favor of its finding that Linz rendered the claimed designs obvious. How can it do this when copying can be “the most probative and cogent evidence in the record”? (see Apple v. Samsung).

d. The Design Patent/Utility Patent Morass

Inexplicably, the Federal Circuit dismissed the differences between design patents and utility patents, saying:

“[T]he coexensiveness requirement [of the presumption of nexus] does not depend on the type of patent at issue. The Board offered no rationale for taking a different approach in design patent cases, and we do not discern any. Accordingly, we reject the proposition that a product satisfies the coextensiveness requirement in the design patent context merely if its unclaimed features are ornamentally insignificant.” (emphasis in original).

The Court veered off the rails here.

It hardly need be pointed out the differences between a design patent and utility patent. A design patent claims the appearance (ornamental) features of a product, while a utility patent claims functional features. In the context of the nexus requirement, it only makes sense that there must be a connection between the evidence of secondary considerations and the appearance features of a claimed design rather than functional features. In other words, unclaimed functional features should not matter in analyzing nexus for a design patent. This is why the Court erred in saying:

“In determining coextensiveness, the question is not whether unclaimed features [of Gamon] are insignificant to a product’s ornamental design. The question is instead whether unclaimed features are “insignificant,” period.” (emphasis in original). It relied again on Fox Factory (a utility patent case in which the unclaimed features are indeed functional).

The Court then made the following, totally illogical statement:

“Because the IQ Maximizer undisputedly includes significant unclaimed functional elements, no reasonable trier of fact could find that the IQ Maximizer is coextensive with the claimed designs.” (emphasis added). The Court’s reliance on unclaimed functional features is clear error.

Moreover, as noted above, the unclaimed features in Gamon’s IQ Maximizer, being the sides of the dispensers - are not visible in normal use, which attests to their lack of ornamental qualities and importance.

Perhaps most disturbing was the Court’s sole footnote in which it said “We do not go so far as to hold that the presumption of nexus can never apply in design patent cases. It is, however, hard to envision a commercial product that lacks any significant functional features such that it could be coextensive with a design patent claim.” (emphasis added). This statement, even though dicta, places most, if not all, design patents at a great disadvantage in obtaining preliminary injunctions, where a showing of nexus is a necessary requirement. This is because most design patents today are for partial designs, i.e., claim only a portion of a product. Design patent practitioners routinely disclaim portions of a design that are deemed insignificant, in the prior art, or easy to design around.

Further, the Fox Factory utility patent case relied on by the Court said that “A patent claim is not coextensive with a product that includes a ‘critical’ unclaimed feature … that materially impacts the product’s functionality…” (emphasis added). Again, unclaimed functional features are of no moment in a design patent, and thus can never be deemed “critical”.

The only elements critical to the product’s ornamental appearance were the front-facing portions, i.e., the label area, the can, and the tabs.

An en banc petition is likely in the offing.