DISTRICT COURT FAILS TO PROPERLY CONSIDER THE PRIOR ART IN ITS NON-INFRINGEMENT HOLDING, INSTEAD CONCLUDING THAT THE DESIGNS AT ISSUE WERE “SUFFICIENTLY DISTINCT”

In North Star Tech. v. Latham Pool Products, the US District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee granted a motion for summary judgment of non-infringement of US Pat. No. D791,966 for a fiberglass pool.

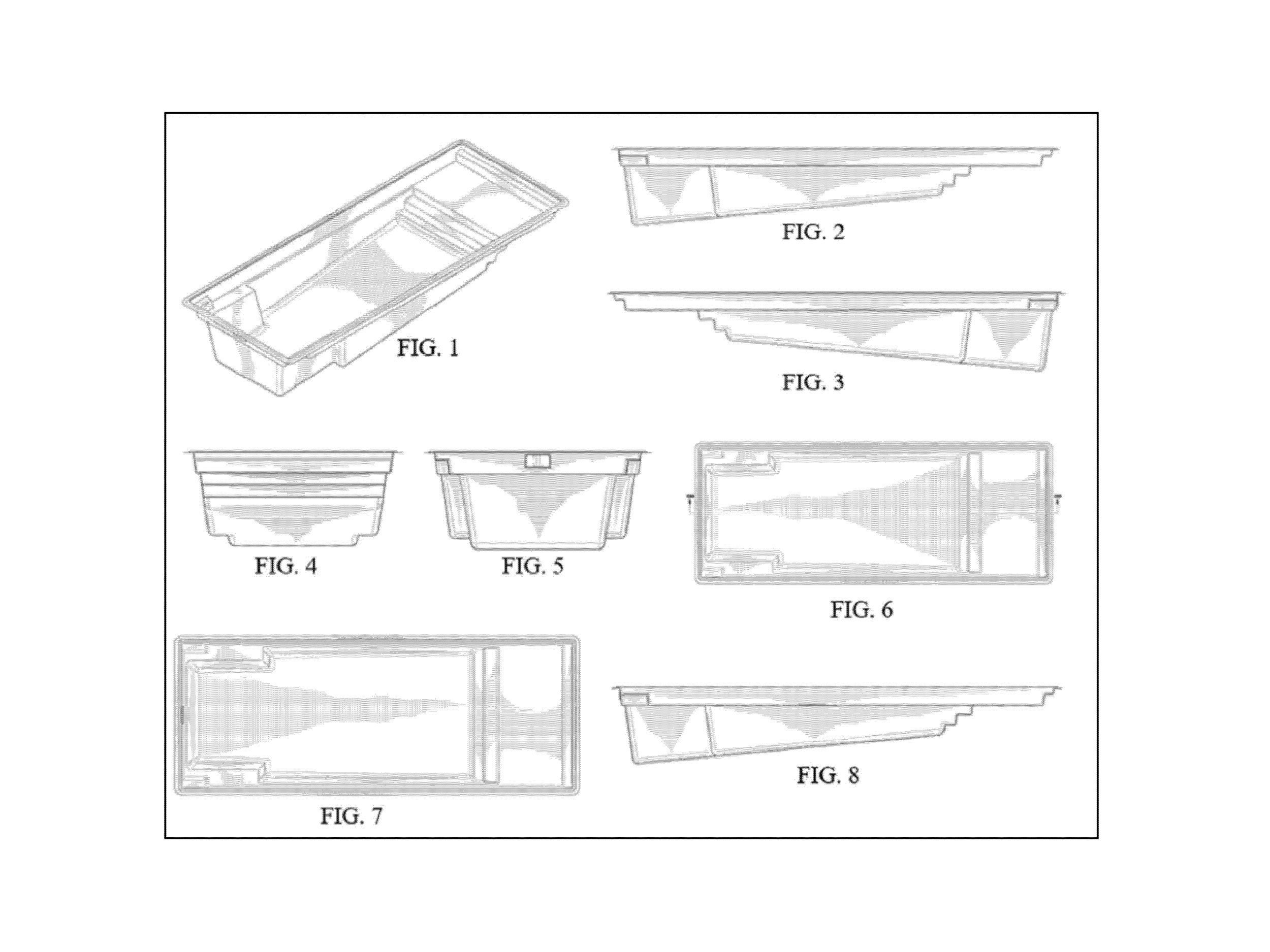

Shown below are drawings from the ‘966 patent, underneath which are comparable views of the accused design:

‘966 Patented Design

Accused Design

In arriving at its conclusion of non-infringement, the court determined that the ornamental appearance of Defendant’s pool is “sufficiently distinct” from and “plainly dissimilar” to the ‘966 patent, citing the test from Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa that is most frequently used by accused infringers to escape liability. Of the several tests for infringement set forth in the seminal Egyptian Goddess case, this is the only one which allows the court to ignore the prior art.

I have long advocated that the “sufficiently distinct” and “plainly dissimilar” tests are unfair and highly subjective because they have no point of reference – the prior art is not considered. Without the prior art, there’s no way to determine if the patented and accused designs are substantially the same. It’s very easy to compare a patented and accused design and identify differences, as did the court. Any 5-year-old can do it. But what’s the frame of reference? If the patented and accused designs (despite minor differences) are closer to each other in their overall visual impression than either is to the overall visual impression created by the prior art, a finding of infringement is usually justified. On the other hand, if either the patented or accused design are closer to the prior art, then a finding of non-infringement is usually justified. But you can’t get there without comparing the overall visual impression of the patented and accused designs to the overall impression created by each prior art swimming pool.

The ’966 patent had nearly 100 prior art references that were considered by the examiner, who apparently felt that the overall claimed design was novel and nonobvious over all of them. It’s true that the sheer volume of the prior art cited during prosecution would require a lot of time to make a design-by-design comparison between each of them and the claimed and accused designs, to see which is closer to which. But it is notable that the court, infusing its opinion with portions of prior art designs, wasn’t able to compare overall appearances, even though the closest prior art cited by the court in the case was very likely provided by the accused infringer.

To its credit, the district court did note in its opinion that even when an accused design is readily distinguishable to an ordinary observer “a full analysis may include a comparison of the claimed and accused designs with the prior art”. However, in this case, the court failed miserably to do so, instead relying on the teachings of disparate individual elements in the prior art to support its non-infringement finding: “Each of the pertinent design elements included in the D’966 patent and [accused design] – from the entry steps to the deep end benches – existed before Plaintiffs filed the D’966 patent.” The court’s cursory analysis of the prior art ignored the well-accepted rule that the designs are to be compared in their entireties, not by individual elements. In the end analysis, it is the overall ornamental impression that is the key to determining whether two designs are substantially the same, not whether individual elements are similar or different.

A proper analysis would have relied upon a comparison of the overall appearance of prior art swimming pools, rather than isolated elements. Such a comparison might have led one to conclude that the patented and accused designs were closer to each other than either was to the closest prior art. I am not saying that the accused design infringed or didn’t infringe the ‘966 patent. But at the very least, the court should have denied the motion and allowed the jury to make this critical factual determination after looking at the patented and accused designs and the prior art.